Highlights from the Presentation

Background

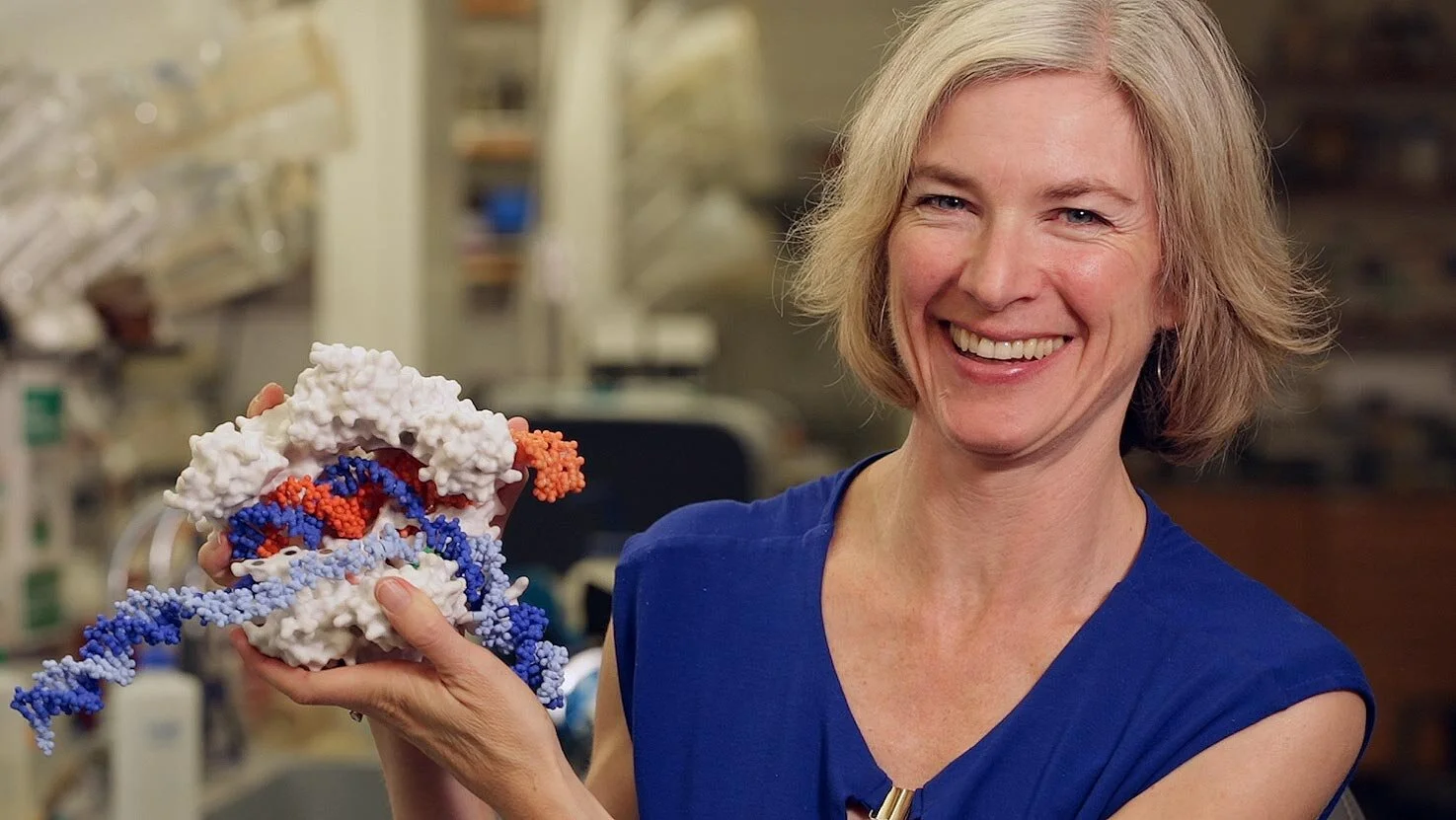

I got into CRISPR as a curiosity-driven small scale side project years ago when we were curious about a set of molecules and pathways that operate in bacteria to protect bacteria from viral infection.

[Referring to a video on screen] …It was these distinctive sequences and bacterial genomes that were first identified by bioinformaticians and were thought to be a signature of some kind of immune response to phage. Although, at the time, it wasn't clear how they operated. We now know that once that genetic record is created, that each include a 20 nucleotide address label, a sequence of 20 letters that matches the sequence of DNA found originally in a virus.

On the Future of CRISPR

I think that it's an extraordinary opportunity to use a technology that happened to come from fundamental curiosity driven research, and yet within a decade we'll have, and already is having, a real world impact on patients.

And remember that this is a therapy that, because it corrects the disease causing mutation that the source is rather than being required as a chronic therapy or treatment, in principle, is a cure for the disease. And so we are very excited to see what will happen in the future as this therapy and the associated trials continue to advance. I did want to point out that there have been some exciting announcements from other clinical trials that were released over the summer, including not only for additional sickle cell and beta thalassemia trials, but also a trial for a disease called transthyretin amyloidosis, a disease of the liver, where CRISPR in this instance was delivered directly into patients for the first time.

…One of the big challenges right now with the technology is how do we make it affordable and accessible to all who can benefit from it? And I know that is something very important to the Foundation. There are other risks associated with the technology we have to really be vigilant and thoughtful about, [such as] the potential for abuse and for unintended consequences. And we have to continually advocate for appropriate support, not only financial, but also appropriate regulatory and legal support as the technology continues to advance, which is happening very quickly.

On Potential CRISPR Application to Tuberculosis, Malaria, HIV, and Cancer Treatment

There's so many opportunities with genome editing. And when we think about addressing TB, malaria, HIV, these are all infectious diseases where one could imagine using CRISPR either to extricate the viral genome from the host, as in the case of HIV. And there are already trials that are underway actually using that type of a strategy. And for malaria and TB, understanding the genetics of the host response to those diseases is, of course, important. [That’s] something that CRISPR can contribute to, as well as potentially allowing programming of the immune system to better deal with those types of infections. And then, for cancer, again, similarly, lots of work underway using CRISPR to understand the genetics of cancer. [It’s] highly complex, but still being dissected, as well as actually thinking about ways to use CRISPR in the clinic, for example, to help with programming immune cells during immunotherapy—and lots more to come.

On Making CRISPR More Accessible and Affordable for Low-Income Countries

It's a really important question and a really big challenge. And I don't think there's a single easy answer to it, but I feel that there's a few things that are really key. One is engagement, just being involved with scientists and other countries. And I'm pleased that at our Institute, even though we're still quite small, we've got active collaborations with folks in South America, with people in Asia, with people in Africa especially around some of the agriculturally focused work that we're doing. But we hope in the end to also be doing work clinically. We just started a partnership with a hospital in Brazil, for example, to extend the sickle cell work that we're doing with some of their patients in the future.

I also think that as scientists, we need to be thinking about how we advance the technology in ways that will make it more accessible. And I'll give you an example with sickle cell disease. As I mentioned, right now, therapy with CRISPR is delivered using bone marrow transplantation. Imagine that we had a way to deliver the CRISPR editing in a way that did not require a bone marrow transplant—that would be extraordinarily enabling and would reduce the cost and the trauma to patients. That's something that we're very actively working on with a whole team of scientists to come up with that kind of a strategy. We're not the only ones doing it, of course. And that's the way it should be. I think that this is a problem that will need many many people to focus on it to try to solve it.

On Lessons Learned During COVID

One thing I've learned really over the last decade that I've been working in this area and coming to the realization that our work could have these profound impacts [is] that I needed to be involved in that conversation, not just watching it from the sidelines. It's been really important experience. And I found that, and I think this will be not news to anyone here, but I think some people are open to new information and to looking at data and thinking about, about scientific technologies from an open-minded perspective, and other people are not.

I've tried to build our Institute in a way that we present ourselves as, we're not advocating for anything here. We're not a political organization. We're a scientific organization. We're a nonprofit. And we provide information. We're educators primarily. And so when you come to our website and you look at our materials, you'll find factual information. And so, for folks that are open to it, that's what they can get.